Victim (1961): The Film That Made Gay History in Britain

“Victim” (1961) is a film about fear – who profits from it, who enforces it, and who finally refuses to live by it.

Why this still matters

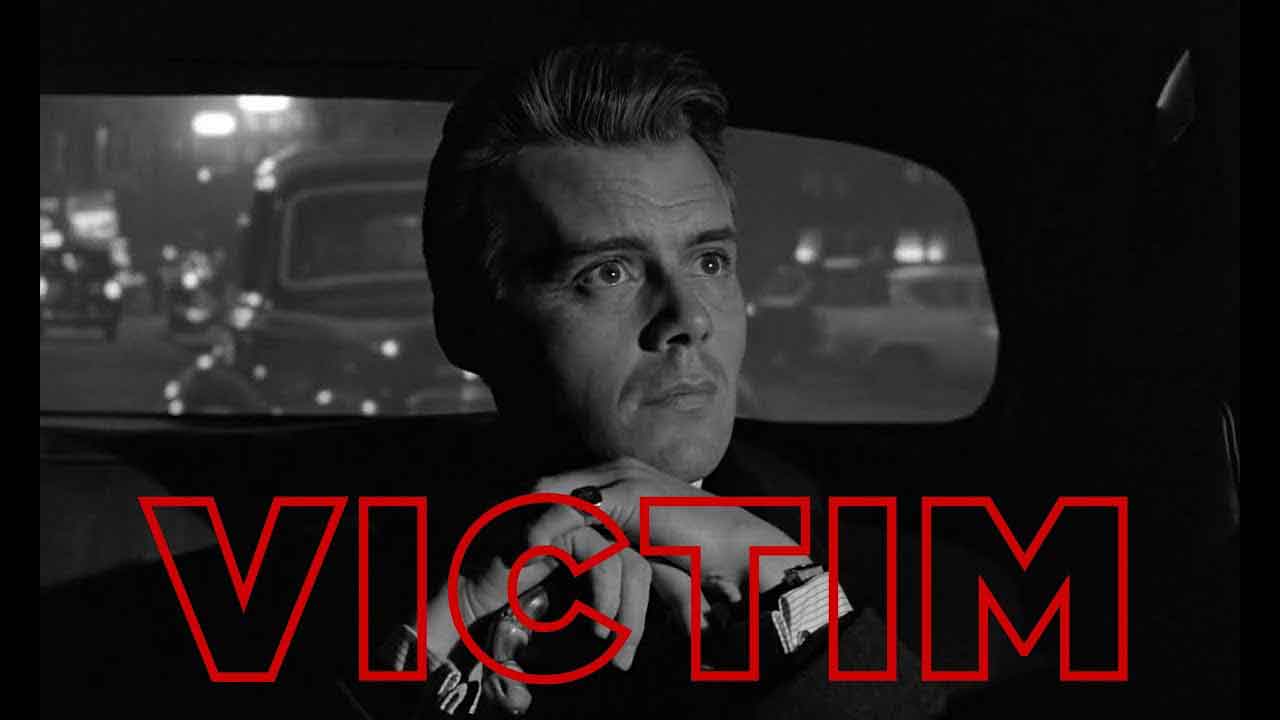

Basil Dearden’s Victim isn’t just a courtroom-adjacent thriller. It is a cool, precise dismantling of a system that made private love a public crime and turned blackmail into a business model. Dirk Bogarde plays barrister Melville Farr with a kind of clenched elegance – a man trained to control every word and gesture who slowly discovers that silence is the most dangerous lie of all. From the opening minutes, the film ties morality to consequence: a terrified young clerk, Jack Barrett, is hounded, cornered, and finally driven to suicide after months of extortion. The police sense the truth but lack the victim’s cooperation – because the law itself has made him a target. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

One of the most modern aspects of Victim is how it treats blackmail. It is not a twist or a single villain’s scheme – it is infrastructure. The film spells this out in clean, procedural beats: demand letters, drops, lookouts, and the calculated use of public shame. An inspector calls the statute that criminalizes homosexuality “the blackmailer’s charter”, and the story proves him right. Barrett steals wages to keep the wolves at bay, leaves almost nothing behind, and then dies in custody. “More victim than criminal,” a policeman says – and the line lands like a verdict on the entire era.

The photograph that undresses a society

The film’s cruel MacGuffin is a telephoto snapshot – Farr and Barrett sitting in a car, a captured intimacy that can be weaponized without a single explicit act. The image passes through the plot like a lit match near dry paper. Farr realizes that Barrett had been paying to suppress the negative, and that his own refusal to listen may have pushed the boy further into danger. The recognition is quiet, almost surgical. No shouting match, no melodrama – just a lawyer studying a piece of evidence that will dismantle his life if he continues to play by the rules.

Marriage, truth, and the cost of composure

Sylvia Syms, as Laura Farr, is the film’s conscience and mirror. Her scenes with Bogarde are devastating because they’re honest about love that exists alongside an impossible truth. Laura wants clarity more than protection. Farr, finally cornered by her compassion, admits the thing he has been resisting – not an affair, but desire – and the air between them changes forever. It is one of the rare 1960s moments where a mainstream film treats a wife neither as a fool nor a martyr, but as a full moral agent.

London as a machine of respectability in Victim (1961)

Dearden frames the city as a maze of polished surfaces and coded warnings. There are offices, bars, salons, and back rooms where everybody “knows” and nobody speaks. A hairdresser sacks up his life to flee to Canada, only to collapse under the pressure; a fading aristocrat wants to pay and keep paying; a matinee idol negotiates for incriminating letters as if he were buying a bespoke suit. Even the threats are tidy – a slur painted in white on a garage door, designed to stain reputations more than brick. The machine runs on secrecy, and secrecy makes excellent fuel.

Dirk Bogarde’s line in the sand

Bogarde’s performance is remarkable not because it explodes, but because it compresses. He plays a man for whom self-control is a profession. Watching that control fail – not into scandal, but into integrity – is the drama. When Farr decides to stop playing along, the film clicks from chamber piece to moral thriller. The final stretch turns procedural again: timed drops, police surveillance, a dingy lair where the blackmailers gloat about “clean minds in healthy bodies,” and finally an arrest that exposes the hypocrisy as common crime rather than cosmic taboo. Farr then walks into the police station to give his statement, fully aware of what that might cost. It is a better ending than triumph – it is responsibility.

What the film actually argues

The film does not ask for tolerance as a favor. It shows the law producing collateral damage: ruined lives, incentivized violence, and a permanent market for extortion. By the time credits roll, the viewer has seen how repression enriches the least scrupulous and humiliates the decent. The inspector’s line about feelings – “I’m a policeman, I don’t have feelings” – is delivered with a dry civility that hides a plea: give us laws we can enforce without abetting cruelty.

Legacy without dust

We often talk about Victim as “important”. It is. But it is also sharp entertainment – paced like a crime picture, performed with immaculate restraint, and photographed with an eye for the way fear sits on a face. Its bravery isn’t in speeches. It is in the choice to put ordinary human tenderness on screen and refuse to label it obscene. That’s why the film still feels current: shame is a recurrent technology, and every generation needs a story that shows how to cut its power.

Verdict: A precise, humane thriller that turns moral panic into evidence – and then prosecutes it. Essential viewing.