By DAVID SHAYWITZ

Our current system of delivering care is awful from the perspective of seemingly every stakeholder. It frustrates, enrages, saddens, and depletes patients and physicians alike. No one designed it this way. It evolved through a series of choices and contingencies that perhaps made sense at the time but now seem to have led us down an evolutionary dead end.

While there’s no shortage of examples, I was especially struck by an anecdote I heard in Dr. Lisa Rosenbaum’s brilliant “Not Otherwise Specified” podcast series for the NEJM. Her focus this season is primary care, and in one episode she speaks with a Denver family physician named Larry Green.

“I practiced in the oldest family practice in Denver, for years,” Green explains. “I was the chair of that department, I directed that residency, and I’m now a patient in that practice. I cannot call it. It’s impossible. Because when I call the practice, I get diverted to a call center…”

From the perspective of what he calls the “medical-industrial complex,” he says, longitudinal relationships are “totally unimportant in healthcare.”

Yet these relationships – developed with care over time – tend to be what many patients crave and what effective doctoring typically requires.

Green’s experience won’t surprise anyone who has tried to get care lately. In November 2023, Mass General Brigham announced it would not be accepting new primary care patients. At hospitals everywhere, it’s not unusual for patients to spend hours on gurneys in emergency-department hallways, waiting for an inpatient bed.

I don’t know many physicians who haven’t struggled to get care for themselves or a loved one – often at the very institutions where they trained and to which they’ve devoted years of their lives. If even insiders can’t reliably access timely, compassionate care, what chance does anyone else have?

The miserableness of the system has been well documented, and physician burnout has sadly become a dog-bites-man story.

Applicants Are Still Flocking to Medical Schools

What’s perhaps more surprising is how many people are still desperate to enter the system and become physicians, fueling an application process that, as Drs. Rochelle and Loren Walensky have documented in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), has become increasingly competitive, expensive, and time-consuming. Premed students routinely take an extra year (or more) to tick all the expected boxes and jump through the hoops that are perceived as mandatory.

This highlights something that’s easy to forget: the ideal of medicine remains deeply attractive. I wrote about this almost thirty years ago in a New York Times op-ed, and it’s still true today.

The notion of doctoring – of being trusted at the intersection of science and human stories – retains a powerful hold on young people. If only the actual experience could live up to the hope of these applicants, the well-worn quotes from Osler and Peabody, the promise of the profession, and the expectations of patients.

Searching For A Better Alternative

The idea that there must be a better alternative is at once familiar and evergreen.

If you’re a cynic, you channel Homer Simpson and conclude, “We tried our best and failed miserably. The lesson is: never try.”

I see it differently.

The persistence of attempts to build something better – despite repeated disappointment – captures both how entrenched the current flawed system is and how deeply people yearn for something appreciably better.

At this point, I don’t know many people who seriously expect incumbents – whether health systems or their core technology vendors – to deliver radical change. Most are too busy trying to squeeze more juice from the existing machinery to welcome disruption.

Without a meaningful incentive, you wouldn’t expect organizations exquisitely tuned to the current equilibrium to dismantle or restructure it.

Even so, some of the most committed innovators I know are doubling down inside health systems, trying heroically — like George C. Scott’s beleaguered chief of medicine in The Hospital — to wrestle these institutions back toward the care they were meant to provide.

Others are exploring promising paths outside.

Starting With an Obvious Gap: Preemptive Care

In the absence of an established alternative, many patients – and many doctors – are trying to assemble at least components of a better system. For a lot of people, that begins with focusing on an aspect our existing system overlooks and undervalues: preemptive care – sustaining our health rather than simply caring for our illness.

As I recently discussed in a Wall Street Journal op-ed and at a Harvard Business School panel on healthy aging, the current fascination with “longevity” sits on top of something more interesting than recovery pods and rejuvenation Olympics. It’s easy, and appropriate, to roll your eyes at anti-aging drips and supplement stacks.

Underneath the spectacle, though, I’ve been struck by a quieter shift. More people seem to believe that the deterioration they’ve observed in older relatives, friends, and cherished mentors isn’t inevitable, and they’re organizing their lives accordingly — an effort, in Bart Giamatti’s phrase (riffing on Milton), to fend off “the ruin of our grandparents.”

Science has helped here. Geroscience has moved from backwater to frontier, and the message it carries is surprisingly simple: movement, sleep, decent food, and warm human connection are not lifestyle accessories, they’re central levers of healthy aging. GLP-1 medicines, as I described in STAT this summer, have added an unexpected assist, giving many people who’d been defeated by years of yo-yo dieting a first experience of real traction.

At the same time, advances in measurement have made the body feel newly legible. Population-scale data have given rise to ideas like “biological age” – an assessment approach not yet validated for clinical use in individuals, but powerful in the story they tell.

Concepts like “biological age” invite people to see aging as at least partially malleable, as something you can potentially inflect.

Even some of the more dubious offerings – supplement rituals, for example – often function less as biochemistry and more as daily expressions of intent.

In the op-ed, I argued that this is the real through-line: a refusal to retreat passively into decline, and a growing appetite for preemptive moves that might tilt the odds, even a little, in our favor.

Aspiring Longevity Contenders: Fitness, Wearable, & Testing Companies

Not surprisingly, this perceived opportunity has attracted several categories of companies into the “health” space. You can roughly sort them into three overlapping buckets:

- Fitness platforms like Peloton and Tonal that started as movement motivators and now increasingly wrap their offerings in a longevity narrative.

- Wearable-centric companies like Oura and Whoop that focus on performance metrics around activity, strain, and recovery, again increasingly framed as healthy-aging tools.

- Comprehensive testing platforms like Function Health, Superpower, and others, which offer large batteries of laboratory tests (often accompanied by imaging) marketed as opportunities to identify vulnerabilities early.

All of these companies are working feverishly on AI-enabled data plays and promise some version of personalized recommendation. Many are led by serious people who genuinely want to help.

Yet taken as a group, they also reveal the limits of an engineering mindset applied to human flourishing. As I argued in a recent STAT column, we’ve become very good at harvesting data and building dashboards, and much less good at building platforms that support the experience of living a fuller, more agentic life.

Fitness & Wearable Companies: An Obsession with Performance Metrics

Today’s digital health tools, as I discussed in the Boston Globe this summer, tend to optimize what’s easy to count and, in the process, miss what most of us actually value: connection, purpose, and the sense that our choices are beginning to add up.

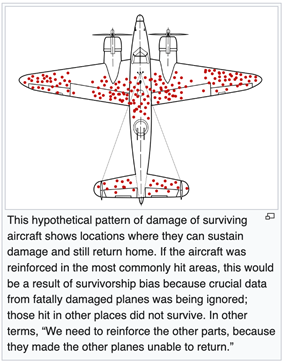

The fitness and metric-heavy companies also illustrate a classic analytic trap (“survivorship bias”) that has been on my mind a lot lately – the “airplane problem.” (Image source: Wikipedia.)

During World War II, analysts studying bombers returning from missions noticed that certain parts of the planes were riddled with bullet holes, and proposed adding armor to those areas. Statistician Abraham Wald pointed out the mistake: the bullet holes marked the places a plane could be hit and still make it home. The planes that didn’t return had likely been hit elsewhere. That’s where the armor was needed.

Most fitness and wearable companies are obsessed with retaining the people who already sign up – generally highly engaged, data-hungry users who enjoy tracking their VO₂ max, heart-rate variability, and step counts. These are the planes that make it back.

What these companies don’t see are the people who try once or twice, feel judged or overwhelmed or bored, and bounce off – people like New York Times op-ed contributor Rachel Feintzeig, who memorably describes her exercise experience:

“I get on my Peloton and am confronted with a veritable dashboard of my inadequacies: cadence (sluggish), resistance level (embarrassing), output (am I even alive?). There is my prior, surely eternal, personal record, highlighted so that I never forget exactly how much better I was three years ago. Suddenly I’m grappling with the passage of time, in my basement, as an Instagram influencer in a coordinating spandex set beseeches me to pedal faster.”

People like Feintzeig – and those who never even bother with platforms like Peloton –are the missing planes, as well as the untapped opportunity.

Early on, I was drawn to the idea of starting with movement as the foundation for a broader vision of flourishing, in part because it’s so concrete, palpable, and obviously useful for health on its own terms, even before it connects to anything deeper.

It reminds me of the famous exchange from Woody Allen’s 1975 film Love and Death:

Sonja (Diane Keaton): “Sex without love is an empty experience.”

Boris (Allen): “Yes, but as empty experiences go, it’s one of the best.”

Movement without any larger sense of meaning can feel a bit like that. Even if it doesn’t yet connect to purpose, agency, or community, it’s still one of the healthier “empty experiences” we have – especially for those who aren’t exercising at all, since the health benefits of going from nothing to something can be as significant as going from something to a lot more.

I still think movement is a great place to start.

Unfortunately, I don’t see much (any) evidence that today’s fitness platforms view longevity as more than a marketing gloss, or that they are preparing seriously to serve the far larger group of people who want to lead richer lives, not dominate reductive leaderboards.

At the end of the day, it seems, fitness companies are gonna fitness. The longevity branding is kosher-style at best, and often closer to a BLT on a bagel.

Comprehensive Testing Companies: False Positives & Sterile Precision?

The comprehensive testing companies raise a different set of concerns. Large panels of lab tests and imaging sound appealing – who wouldn’t want to “know everything” and catch problems early?

In practice, as Dr. Eric Topol has critically reviewed at Ground Truths, the risks of false positives and incidentalomas are substantial, especially when testing is decoupled from clear, evidence-based action plans.

I’ve spent years following the arc from genetics to “personalized” to “precision” medicine and since high school have been deeply engaged in the science. I have a real appreciation for the promise, as well as for the practical limitations.

I recognize that the opportunities for truly precise, individualized interventions tend to be wildly overstated – even the ones that don’t come bundled with the hard sell of supplements.

The same goes for metabolomic and nutritional profiling. As Kevin Hall and others have pointed out, much of what’s been sold as precision nutrition turns out to be better marketing than science.

So where are the rays of hope? Mostly, they center around talent as much as vision.

Green Shoot 1: Talent Redefining Testing Companies

When Function Health announced its recent fundraise, most of the attention focused on the celebrity investors and marketing sizzle.

What caught my eye was something else entirely: the decision by Dr. Daniel Sodickson –- a serious scientist and imaging innovator, long a leader in MRI at NYU, and recently an author –- to join as Chief Medical Scientist.

Dan, also a medical school classmate and friend, is the opposite of a hype merchant. He is thoughtful, technically deep, and obsessed with context and longitudinal understanding. His move signaled to me that Function was serious about building an engine for interpreting multimodal, longitudinal data in a way that could, over time, support genuinely more precise, personalized recommendations.

This aligns closely with ideas the exceptionally innovative medical scientists Lee Hood and Nathan Price have been articulating for years (including in their visionary 2023 book, The Age of Scientific Wellness), and that efforts like Arivale tried to operationalize. I’m excited about this direction and have been working with Dan and Nathan on some of these concepts – stay tuned.

Green Shoot 2: Talent Focused on Leveraging Agency & Personal Health Data

A second source of energy and inspiration for me, also connected to talent, has been the caliber of physicians and physician–scientists who’ve reached out to me as I’ve been developing and championing the concept of agency as the “motivational currency of behavior change,” ideas provisionally, and loosely, organized at KindWellHealth.

In just the last few weeks, I’ve heard from clinicians, informatics leaders, former regulators, and population-health experts who said some version of: “Your focus on agency is exactly what I’ve been circling; I’m trying to build my next chapter around something like this.”

These are not people chasing the latest wellness fad. They are serious medical innovators who care deeply about science and patients and are trying to find a way to enhance health that feels truer to both, supported by rigorous, credible evidence.

One direction this naturally leads is towards a health system built around a data-empowered person who becomes the central locus of both control and information. In this vision, you would control your data the way you control your money. You might have accounts at many institutions, but you see everything in one place and can direct it where you want.

This idea has been around for a while, but it has acquired new urgency as patients are increasingly handed more responsibility without real visibility.

A personal “health data cloud” (Nathan Price has been using the more expansive phrase, “personal, dense, dynamic data cloud”) isn’t a cure-all, but it feels like it could be a vital first step towards a more enlightened, informed, person-centric, and humane health future.

It’s important to emphasize that “person-centric” doesn’t mean a series of dispassionate transactions with healthcare providers, which arguably is already the status quo. Nor does it mean dumping a stack of options and PDFs on patients and congratulating ourselves for “empowering” them.

As Atul Gawande has described so eloquently, in appropriately pushing back against medical paternalism, the pendulum in some settings has swung too far the other way.

Some physicians, trying to be sensitive, have misunderstood the assignment. They present a neutral menu and maintain distance at moments when some patients are desperate for a clinician to share the decision-making burden – to listen carefully, offer a considered recommendation, and shoulder some of the responsibility.

As Gawande wrote in 1999, with his usual magnificence,

“The new orthodoxy about patient autonomy has a hard time acknowledging an awkward truth: patients frequently don’t want the freedom that we’ve given them. That is, they’re glad to have their autonomy respected, but the exercise of that autonomy means being able to relinquish it.”

While we might substitute the term “agency” for “autonomy,” Gawande’s point is essential and should be reflected in any future vision of an improved health system.

Green Shoot 3: Talent Focused on Enhancing Agency Itself

A third promising area involves focusing explicitly on agency itself – which is how I view the efforts of companies like Lore (where I serve as an advisor), SlingshotAI, and others. These groups (who often have attracted exceptional talent) start from the psychology of behavior change. They ask how we might help people feel more able to influence their future for the better, and how we might compound that sense of agency over time.

Moving Forward

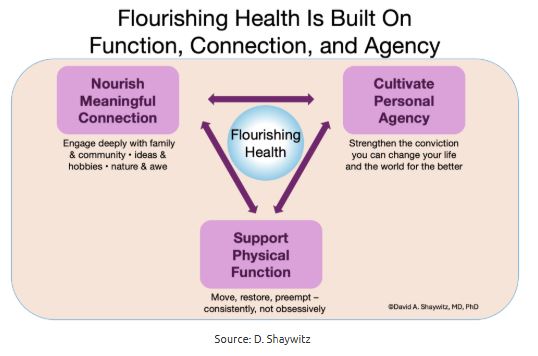

My own conviction is that maximal impact will require integrating this agency focus with two other elements I’ve been writing about: the quantitative side of biometrics and the qualitative, often neglected sphere of connection and meaning.

As I see it (see diagram above), our shared goal is flourishing health, supported by three mutually reinforcing domains: physical function, meaningful connection, and personal agency. A few companies touch pieces of this map. Almost no one designs against the whole thing.

To me, the combination of a strong sense of conviction that this is what the future of health needs to encompass, together with a sense of uncertainty about how we’ll get there, is what’s so exciting, particularly given the remarkable amount of talent that seems to be drawn in this direction. Certainly, this pursuit feels more satisfying than developing innovations aimed at maximizing billing, or escalating the AI battle between health systems seeking reimbursement and payors seeking to deny it.

Patients – and those who are eager to avoid becoming patients – are (as usual) leading the way.

We owe it to them to meet them where they are and — with technology as an aid, evidence as our guide, and compassion as our soul — build an approach to health and healing worthy of the ideals that drew, and continues to draw, so many of us into medicine.

Dr. Shaywitz, a physician-scientist, is a lecturer at Harvard Medical School, an adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and founder of KindWellHealth, an initiative focused on advancing health through the science of agency