Ten-cylinder engines, particularly V10s (the most common layout for 10s, though there have been attempts at flat-10s and even W10s), have some interesting engineering, packaging, and power-delivery quirks. But that can all wait, because listen to this:

That is the exhaust note of the V10-powered Lexus LFA. If you’re unfamiliar with that car, oh, you lucky so-and-so, you’re going to learn about what may be the most stupendously sonorous, sensous, spine-tinglingly sweet-sounding cylinder count there is. Yes, the Lexus LFA had exhaust-note tuning assistance from Yamaha (both the one that makes motorcycles and the one that makes pianos), but there’s something inherent in V10s that tickles our brains just right.

Scott Mansell, former EuroBoss racing champ and founder of YouTube channel Driver61, did a deep scientific dive into why V10s sound so good, particularly the 20,000-rpm Formula 1 V10. He showed that as engines gain cylinders, new frequencies get accentuated. My fellow musicians already see where this is going: Once an engine hits cylinder five, you get a major third interval, which sticks around as the cylinder count doubles to 10. Humans generally find that major intervals sound happy, so V10s can be scientifically proven to delight our ears. Even a diesel version, like that found in the nightmarishly complex Volkswagen Touareg V10 TDI, can sound amazing:

Okay, enough gushing over how V10s sing — now down to brass tacks. Something else Mansell said about V10s rings true, and that’s that they encompass lots of compromises. Anyone who’s ever compromised knows you have to give something up to get something, and V10s both giveth and taketh away.

V10 pros: Goldilocks zone-sizing and vertical balance

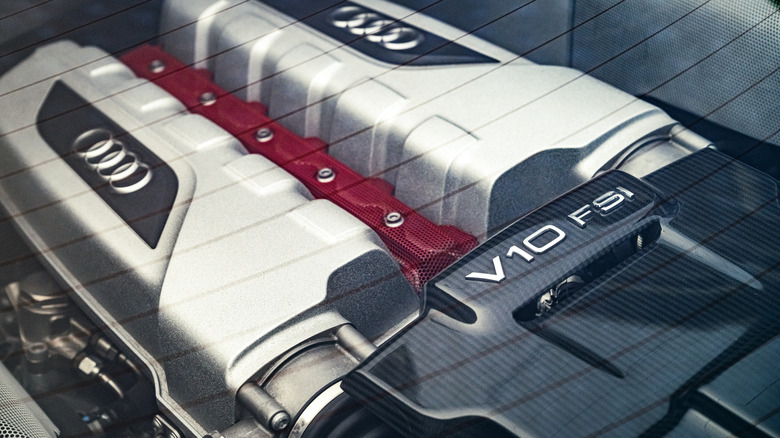

V10s live in the “Goldilocks zone,” so named for the fairy-tale protagonist who thinks it’s a good idea to break into houses owned by bears to find things that are “just right” — not too big and not too small. Slotting neatly between V8s and V12s, V10s offer enough advantages that Formula One engines went from V12s, V8s, and V10s to just V10s for about eight years.

Let’s compare them to V8s first. Most obviously, more cylinders means higher possible power. Plus, V10s can spin faster. Compare a 5-liter V8 with a 5-liter V10, and you’ll see the V10’s pistons and rods are smaller, letting it rev more freely thanks to lower reciprocating mass per cylinder. While higher revs don’t automatically mean more power, the potential is there with better-breathing hardware. And with power strokes every 72 degrees of rotation, even-fired V10s can be quite smooth (more on even and odd firing momentarily).

Now for V12s. V10s are typically smaller and less fuel-thirsty. Smaller makes sense, as 10 is a lower number than 12, and complexity also is obvious, as V12s have 20% more cylinders than V10s. But the fuel consumption difference is more complicated. More cylinders use more fuel, sure, but there’s another efficiency enemy: friction. Those extra two cylinders need lubrication for their associated parts, including the crankpins, journals, pistons, valves, lifters, etc. V12 cooling systems must be beefy to keep everything from going molten. Also, let’s say you have a V10 and V12, both with a 4-inch bore and 3-inch stroke. The V10 will displace 377 cubic inches and the V12 will displace 452, but the V10 will have less reciprocating mass (two fewer pistons/rods) and less rotating mass (shorter crankshaft), meaning it can spin up more quickly.

V10 cons: Side-to-side hustle, size can be just wrong

A warning: here be technical info. Some V10s are “even-firing,” providing a power stroke with every 72 degrees of crankshaft rotation (like the Lexus LFA):

V10s can also be “odd-firing,” where power strokes ping-pong between 54 and 90 degrees (like in the Dodge Viper):

Typically, even-firing V10s use 72-degree vee angles, while odd-firing V10s use 90-degree vee angles, though 18-degree split crank pins can make 90-degree V10s fire evenly (like in the Lamborghini Gallardo, which is old enough to restomod now). So, here’s the first V10 issue: balance.

While even-firing V10s have good primary and secondary balancing, they wobble because of rocking couples. In a Ford Triton 6.8-liter V10, for example, after cylinder six fires, the next one is cylinder five, on the opposite bank at the other end of the engine. Open up the driver’s side valve cover on that Ford V10 and you’ll see a massive balance shaft to fight those shakes. And while odd-firing V10s don’t need balance shafts, they have another vibration source: that eternal switch between 54- and 90-degree firing. You can fight the roughness of odd-firing V10s by putting rev-unhappy counterweights on the crankshaft, adding vibration dampers, or ignoring it and turning up the radio.

Finally, here’s where the Goldilocks zone gets flipped on its head. V10s are larger, more complicated, and thirstier than V8s, which you can just turbocharge or hybridize for more power. As for V12s, well, they’re inherently way smoother than V10s. This is the real crux of why V10s are gone from passenger cars. Automakers would rather just hybridize or turbocharge a smaller engine and get better EPA fuel ratings with less size, weight, and engineering complexity. Sorry, V10s, we’ll always miss you.