There are conflicting stories about beer cheese’s golden-orange origins. It appears to have first been served in the 1940s at a restaurant in Clark County, Ky., called Johnny Allman’s (since renamed Howard’s Creek). In 2006, when Kathy Gorman Archer, president of Howard’s Creek Authentic Beer Cheese, decided to revive the spreadable cheese brand—to widespread acclaim—she said it initially was a sustainable effort: leftover sharp cheddar cheese was a key ingredient, as well as leftover beer.

“Allman’s love of southwestern flare is probably why there’s cayenne pepper, as well as garlic and other spices, in the recipe to kick it up,” Archer said about the model that has defined beer cheese in the U.S. for over a century. But nowadays, paradigms are shifting, from the tangy, spicy snack to a new category forged by American farmstead cheesemakers, incorporating beer into their cheeses from the start.

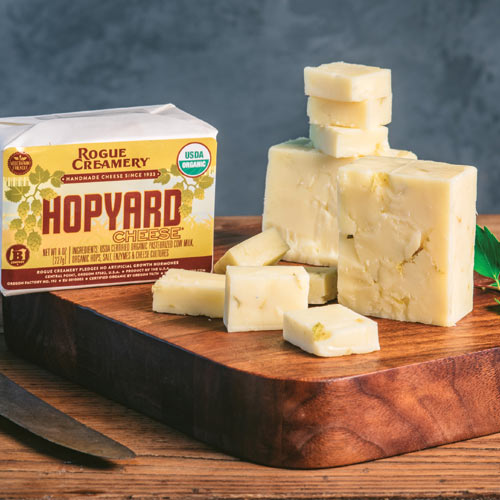

Going Rogue

Many have associated Oregon’s Rogue Ales with Rogue Creamery, though they are related by name only, since the brewery was located only four hours away from the creamery (it announced its closure in November). Every five years or so, Rogue Ales produced an anniversary ale for the cheesemaker, meant to be drunk alongside offerings such as their signature Oregon Blue, the first cave-aged cheese west of the Mississippi, established in 1953. Rogue Creamery produces a Chocolate Stout Cheddar with Hopworks Brewery from Portland, Ore., and has for nearly a decade. This was part of Rogue Creamery’s principle: to pair a certified organic brewery with their organic dairy.

Marguerite Merritt, cheese emissary and brand manager of Rogue Creamery and a certified sommelier, describes their savory, sweet approach to the polarizing blue cheese style as “not overpowering, but bitter and strong.” Though this lends itself to cheese boards and salads, as it’s not as intense as a standard Danish blue, it’s Rogue’s innovations, such as their hazelnut shell-and-alderwood cold-smoked version, that inevitably found them experimenting in the beer cheese category.

For the chocolate stout cheddar, the beer is added to the cheesemaking process just as the whey is beginning to separate from the curd, infusing the milk and curd with a nice balance of flavor and subtle maltiness. The cheese doesn’t wind up tasting exactly like the beer, but what it adds is a sweet, malty, and marbled effect. Their chocolate stout cheese turned out to be a jumping off point for crafting Hopyard, a cheddar style made with fresh, local Northwest-grown hops. The hops are mixed with curds while setting, similar to the chocolate stout cheddar process, but this time without any beer. It has a strong following and is only sold direct to consumers. “The floral bitterness of the hops makes it really fun to pair with an IPA in particular,” Merritt said, reinforcing the citrus, pine, and earthy appeal of a West Coast style, but in cheese form.

A Beer Cheese Journey

Another West Coast dairy gleaned inspiration from its surrounding beer scene as well. Fiscalini has been operating as a dairy farm in Modesto, Calif., since 1914. In 2000, they added a line of farmstead cheeses, mostly cheddars, all made by hand. What sets Fiscalini apart, explains fourth-generation owner Laura Genasci, is that they only use milk produced from their own cows.

Committed to traceability, Fiscalini Craft Beer Cheddar is made with Black Blizzard Imperial Stout from Dust Bowl Brewing, headquartered in Turlock, Calif., only 20 minutes down the road. Genasci went to college with one of the owners of the brewery, whose family is in the dairy industry as well. The beer is roasty, with notes of coffee and chocolate, as is the cheese.

Fiscalini’s beer cheese journey started with Hopscotch, a cheddar made with Scotch ale. Beer was mixed in with the curds before forming them into 40 pound blocks. Pressed overnight—which infuses the beer even further—this process gives the cheese its mottled pattern, and “so you get beer flavor in every single bite,” explains Genasci.

“We think about our beer cheddar as a culinary collaboration where the artistic work of brewmasters and cheesemakers collide,” says Alex Borgo, Fiscalini’s cheesemaker. During the beer brewing process, malted barley is mixed with water and heated to activate the enzymes in the grain. Similarly, during the cheesemaking process, Borgo selects a special starter culture for its microbial enzymes that help activate the separation of curds from whey once rennet is added to the milk.

Many stout beers, such as milk stout, are rich and creamy with a smooth texture, and cheddar cheese is commonly sharp and tangy. “The combination of the two results in a cheese that is rich, tangy, and malty, with a complex flavor—we age our beer cheddar three months, but the more age the cheese gets, the stronger the cheddar and beer flavors become,” says Borgo. Similarly, for special occasions, Rogue squirreled away some two-year reserve for a bigger, more robust flavor, as can be found in a stronger beer.

Collaboration

It’s not all about big beers, though. Giant Food Stores, a Pennsylvania grocery chain, propositioned Caputo Brothers Creamery in Spring Grove, Pa., to stock its shelves with local beer cheeses. Caputo, which started its artisan cheese business in 2011, only made Italian-style cheeses at the time.

Giant noted that they’d already been talking with Tröegs Independent Brewing as a potential partner, says Caputo Brothers’ co-founder, Rynn Caputo. “If you drew a line from Tröegs to us to Giant’s HQ, the dairy farms sat right in the middle—three [Pennsylvania] businesses trying to make something that would have a direct impact in our region.” Though they had sworn to never make a cheddar, Caputo was willing to try a gouda.

Troegenator, a double bock and Tröegs most storied beer, already had a cult following and in the cheese, it brought out a noticeable sweetness and golden color. An entire keg is used for a batch of the cheese, which became Tröegs’ largest social media hit in 2019.

“People started immediately asking for other beer (cheeses),” says Caputo. They went on to make cheese with Tröegs Perpetual IPA and then Mad Elf, an 11% Belgian holiday ale with notes of cherry, cinnamon, and chocolate. After marinating the curd in an amber pool of the beer, a concoction of cocoa, cinnamon, espresso, and more beer is rubbed into the rind. “The end result makes for a cheese that looks like a slice of chocolate cake,” says Caputo.

For the Perpetual beer cheese, Caputo had the idea of dry hopping milk with the same Citra hops that go into the beer, producing an intense hop milk. “It tastes like you’re eating a beer,” said Caputo. After Caputo salt-water brines the cheese for a couple weeks to help form a rind and preserve the cheese itself, the rinds are sprayed with even more Perpetual IPA. All told, Caputo Brothers uses a case of beer for every 80 wheels produced.

The real key to working with beer (and cheese) is pH, a scale that addresses whether something is acid or base; milk’s pH is around 6.4 to 6.8. Too high a pH (past the low 5s), the curds won’t bind together, while too low (below 4), they’ll get rubbery. Caputo has this process down to such a science that she started a side business called Custom Cheesemakers, which makes custom beer cheese for breweries all over the country.

Although Indianapolis cheesemaker Tulip Tree Creamery doesn’t add craft beer to curds, they too customize cheeses by washing the rinds with a combination of bacteria cultures, beer, water, and salt, permeating each wheel with the essence of the chosen brew. Laura Davenport, co-owner and director of education and sales, credits her business partner’s Dutch upbringing for nurturing their washed-rind cheese pursuit.

Every few weeks, in conjunction with the likes of Sun King, Standard Deviant, Big Lug (highlighting their Pirate Cat porter), and Centerpoint (using their black porter), Tulip Tree was making a new hops beer cheese with another local brewery. Two and half gallons of beer was enough for about 20 to 25 wheels of cheese, each weighing approximately four to five pounds for a double cream style, a departure from the harder cheddar styles mentioned above.

“I’m a beer drinker, an IPA fan,” Davenport affirms. “I love 3 Floyds Zombie Dust [from Munster, Ind.] … but for cheese I’m not looking for something super bitter in the 40 to 50 IBU range.” Instead, Davenport suggested 3 Floyds JinxProof Pilsner.

Beer Cheese in the Big City

Just over state lines, Urban Stead, based in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, opened in 2018. Co-founder Andrea Robbins and her husband are both from Dayton, Ohio, the grandchildren of dairy farmers. They noticed there are fewer than five urban creameries in the United States, a list that includes Perrystead Dairy in north Philadelphia and Beecher’s in Seattle’s Pike Place Market, and they wanted to honor Cincinnati’s deep German roots.

“Early German settlers saw the Erie Canal and likened it to the Rhine River, and we really wanted to make quark, a fresh Eastern European-style farmer’s cheese,” Robbins said. Although Urban Stead has a following for its Street Ched, an award-winning English-style clothbound cheddar, they decided their first foray into a beer cheese would be a Kentucky style.

Braxton Brewing’s Storm Golden Cream Ale, from across the border in Covington, Ky.—near where Robbins’ family had a vacation home where she first fell in love with beer cheese—adds a subtle corn and spicy hop presence to the pale straw-yellow mixture. “It’s kind of the texture of ricotta meets cream cheese—it spreads like pimento, chefs stuff pasta with it, and it’s wonderful for baking.” Robbins even suggests using it in place of mozzarella for a caprese salad or sandwich.

Because it’s a fresh cheese, there’s no time lost to aging. “We get 9,000 pounds of milk a week, and use 1,500 pounds for a batch,” says Robbins. Two to three days later, customers get their beer cheese quickly and it helps balance the cash flow perspective from cheddars and goudas, some of which age for 20 months.

“We serve it with German Swabian-style soft pretzels at the shop,” states Robbins, who suggests the same golden cream ale it’s made with to wash away any spice left on the tongue, a palate cleanser perhaps. But beer isn’t just meant to wash away flavors; in cheese, it can also be something to savor.

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.