“I have seen first-hand the devastating impact that systemic racism and injustice has on people’s lives. I have lost family members to these inequalities. My commitment to this agenda is personal, as well as professional and moral.”

These are the words of Dr Jacqui Dyer MBE who wrote a blog for NHS England last month as part of black history month. She described how the mental health system has consistently failed Black and racially minoritised people. She was writing not only as NHS England’s Mental Health Equalities Adviser and Chair of the Advancing Mental Health Equalities Taskforce, but as a person with lived experience and a carer for those around her.

It is both tragic and shocking how clearly the evidence tells us that, not only do people from minoritised communities experience more mental health problems, but mental health services are also less likely to offer a helpful and healing experience to them. In the UK, people from Black and Minority Ethnic communities, as well as migrants have been found to experience more barriers to accessing mental health services, more coercive and oppressive forms of service provision, more contact with criminal justice services and worse long term outcomes than White British people. Not only this, but evidence also finds worsening patterns of ethnic inequalities in pathways to psychiatric care (Halvorsrud et al., 2018). As Jacqui Dyer summarised:

review after review, stretching back over 4 decades, has told the same story: harsher, more coercive, and less therapeutic care.

Prof Kam Bhui and colleagues (2025) set out to examine the lived experiences of people from racially and ethnically diverse communities who experienced compulsory admission and treatment (CAT). The study analysed the life and care experiences of racially and ethnically diverse people who experienced CAT, using this to inform more preventative, equitable approaches to mental health care. It formed one part of the wider Co-PACT study.

“Admissions could be preventable if access to crisis services was quicker / better pathways into support services”

Methods

The authors noted that “there are very few qualitative studies of CAT, and none that are experience driven and that capture the experiences of ethnically diverse groups” (p.2). They sought to remedy this by using a participatory method known as PhotoVoice.

They recruited participants who had experienced CAT under the Mental Health Act within the last two years. The 48 participants who completed the study came from eight locations across England, which included urban and rural areas and diverse social economic contexts. Participants were purposefully recruited from diverse ethnic groups, as well as representing different ages (ages 18-65), an equal distribution of males and females (M=24, F=24) and different sections within the Mental Health Act.

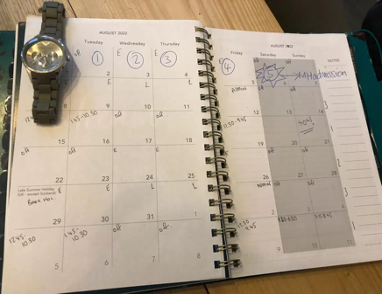

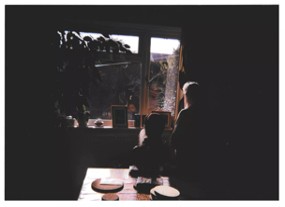

PhotoVoice is a method that invites participants to take photographs, which describe an element of their lived experience. In this study, participants were supported to understand the method and then were invited to describe, reflect on and caption their images over two workshops. This process resulted in three types of data: first, demographic and ‘roadmap’ information detailing individual’s life events in a timeline; second, 535 images and captions; and third, 32 hours of recorded narratives.

Because of this diverse data, the authors used an approach called polytextual thematic analysis (PTA). It allowed them to organise, compare and summarise multiple data forms in one process. Notably, the analysis drew on lived experience approaches, using peer researchers and reflexivity around the dynamics of each researcher’s identity, especially in relation to race and racism.

“Instead of being detained in hospital its better to see the Home Treatment Team. I prefer that because I’m still in the community. Being detained is the same as prison because you’re not allowed to go nowhere.”

Results

As you can see from those featured here and in the full library, the images generated through the study by participants are testament to the power of PhotoVoice in evoking the lived experience of people who participate. Each is accompanied by an extract from the participant to set the context.

Through analysing the ‘roadmaps’ that were created by participants, the study found a significant proportion reported multimorbidity (having two or more long term conditions at the same time), adverse childhood experiences and having carer roles. This is important in framing the other findings; alongside their experiences of compulsory admission and treatment (CAT), participants were coping with other areas of need including theirs and their family’s physical health and the lasting impact of adverse childhood experiences that made CAT and police involvement especially traumatic.

Alongside the images and roadmaps, 5 themes resulted from the polytextual thematic analysis:

- Awareness and prevention

- Compulsory admission and treatment (CAT) process

- Coercive care and staff interactions

- Therapeutic environment

- Specific insights.

Within these themes participants shared their experiences of the process of compulsory admission and treatment. This began by describing how often they were aware of their own mental health deteriorating and sought support but were not offered any, leading to being admitted in crisis. The CAT process itself was dependant on bed availability rather than need, and participants sometimes described being admitted hours away from their local community, in environments that were noisy and sometimes lacking in facilities.

Participants experienced a huge variation in the skills and experience of the staff that supported them, with many participants describing coercive care, sometimes with staff members being racist, rude, hostile and openly threatening to them. Some participants described the dearth of interactions during their admission, with conversation only taking place while administering medication or providing meals. They needed more communication, in different forms, about what their options were and what they could expect during their admission.

There were positive experiences for some participants, who appreciated the activities that their ward provided and described compassionate staff, especially in community services following their admission.

The ‘specific insights’ spoke to the participants’ largely negative experiences of emergency departments and police involvement, which left them feeling criminalised, embarrassed and ignored. They spoke about the elements of care they wanted more of, including advocacy, culturally sensitive formulation, better supported transitions to community care, family involvement, and recognition of adverse life experiences as well as the impact of social contexts and biographies.

In sum, most participants had deeply negative and sometimes traumatic experiences of compulsory admission and treatment. While there were positive elements to the care they received, the study highlights the epistemic injustice and racialisation in care processes.

From their findings, the authors developed a logic model (see figure 2), summarising the approaches that could be used to improve the experiences of people subjected to CAT, including advocacy, trauma informed and culturally sensitive assessment processes.

“This symbolises the journey of being taken to hospital. The first time I was sectioned I was taken to hospital in a black van by three people not wearing uniforms. I thought I had been kidnapped. It was scary, confusing and lonely. It’s like a journey into the unknown.”

Conclusions

- The study found that participants experienced epistemic injustice, being discredited because of their race and mental health labels, as well as having little access to sources of support and connection.

- The authors argue that new models, including preventative, trauma-informed approaches are needed not only in inpatient services but across communities, in general health care, and social services.

- They advocate for the use of shared decision-making and advanced directives to support prevention and build trust, as well as better integrated care in order to tackle stigma and offer cohesive support.

“Banging your head against a brick wall… Sometimes I find mental health care/accessing mental health care can be like hitting your head against a brick wall. Being detained is all well and good… as long as there’s a bed for you. Which often there isn’t. I’ve been on the ‘bed list’ for 5 weeks now (for informal admission this time). Multiple weekly incidents, police and ambulance involvement… and still…. ‘No beds’.”

Strengths and limitations

It is refreshing to read research that so clearly centres lived experience of participants and researchers. The use of peer researchers, lived experience contributors and the acknowledgement of the authors’ own identities within the research demonstrates the importance of lived experience alongside reflexivity.

The use of PhotoVoice gave participants the opportunity to communicate their experiences without words, and foregrounded experiences from people that have historically been marginalised or dismissed. The resulting images offer a powerful, sometimes visceral insight into the emotional, relational and racialised dynamics of detention under the Mental Health Act.

In their analysis of the data, the researchers wove lived experience interpretations through the process and stressed that they paid attention not only to common patterns but also to uncommon experiences, enabling a more nuanced account of what coercion feels like in practice for people subject to CAT.

While the findings of the paper are clear, parts of the findings section feel repetitive, perhaps speaking to the difficulty of analysing so many data sources. Leading on from this, the discussion of the findings could have been more ambitious:

- Despite the strong findings around racialisation, institutional mistrust and structural inequality, there was no commentary on the systemic reforms required to address institutional racism in mental health services.

- The logic model is helpful, but it stops short of the more radical, structural critique that the data seem to call for.

- The omission of the Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) is particularly striking, given how closely participants’ accounts align with PCREF’s focus on racialised disparities, accountability and culturally capable care.

Another limitation concerns the inclusion of White British participants. While the authors aimed for ethnic diversity, it is unclear why any White British participants were included in a study explicitly focused on racialised experiences of detention. To me, their presence risks diluting the experiences of structural and institutional racism that the other participants were able to share.

“I was treated differently in a BAD WAY is it because of being Asian?

I was voiceless I couldn’t speak up due to the mental illness i.e. Acute Anxiety – clinical depression.

Loving parents helped me to get better.

Love and support of everyone who helped me get better apart from the ones in the mental centre.”

Implications for practice

The findings of this study offer timely insights for practice within mental health services. In her blog, Jacqui Dyer reminded us that efforts to embed racial equity into the next chapter of the NHS must move beyond good intentions into accountable action, and this study offers some guidance on what that might look like.

In terms of practice and delivery, it is clear that services need to adopt more overtly anti-racist, culturally grounded practices that are co-designed with people with lived experience of racialised detention. This could include peer-led approaches, and support to navigate services, especially alongside other health conditions or caring responsibilities.

The findings could also inform staff training, which needs to move beyond awareness raising to build capacity for corrective organisational action, and the development of specific skills around cultural sensitivity and trauma informed care.

In terms of research practice, this paper shows the importance of qualitative studies on this topic. One of the greatest strengths of this study was it’s foregrounding of lived experience, which evoked the often traumatic experiences of participants.

These stories, and the photos that accompany them are difficult to ignore and could be used to inform changes in practice, both in health and social care services, and within research.

The Co-Pact PhotoVoice exhibition took place around the country so that clinicians, policy-makers and people with lived experience could view the images and quotes and consider the impact on their work and lives.

Statement of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest relating to this study. AI was not used to support the writing of this blog post.

Edited by

Simon Bradstreet.

Links

Primary paper

Bhui K, Mooney R, Joseph D. et al (2025) Racialised experience of detention under the Mental Health Act: a photovoice investigation. BMJ Mental Health 28(1): 1–9.

Audio documentary

Listen to the Co-Pact exhibition audio documentary that the Mental Elf made for the Co-Pact project.

Other references

Dyer J. (2025) Hope, progress, and accountability: Tackling racial inequalities in mental health together. NHS England blog, 28 Oct 2025.

Halvorsrud K, Nazroo J, Otis M, et al. (2018) Ethnic inequalities and pathways to care in psychosis in England: a systematic review and meta- analysis. BMC Medicine 16:223.

Photo credits

All images are the original work of the research participants (rights reserved) with accompanying notes provided by them to provide context to each image. The full Co-Pact image library is available here.